NEW! Piano Inspires Podcast:

Tune in to listen to our inaugural interview series on the transformative power of music.

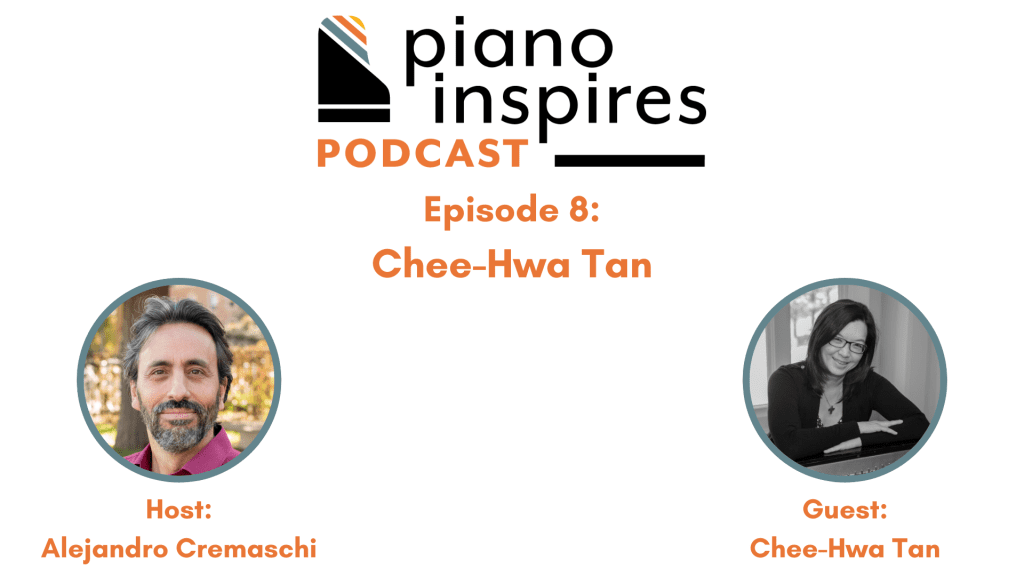

- Episode 8: Chee-Hwa Tan, Composer, Pianist, and Teacher with Alejandro Cremaschi

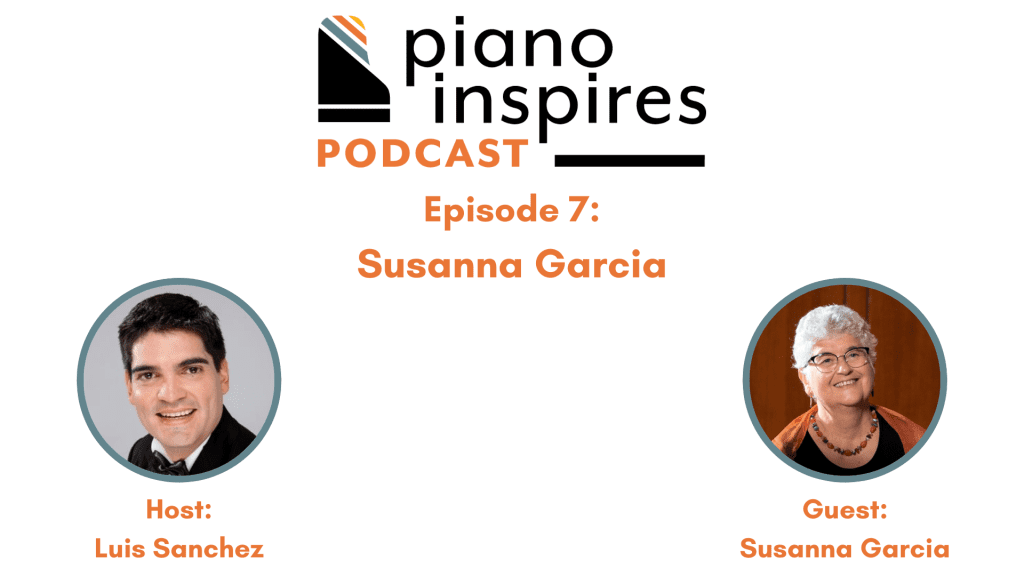

- Episode 7: Susanna Garcia Discusses DEIB with Luis Sanchez

- Episode 6: Connor Chee, Navajo Pianist and Composer

NEW! Piano Inspires Discovery:

A space dedicated to inspiring the love of piano and music making through educational and inspirational content.

- Piano Inspires Podcast: Chee-Hwa Tan

- 2024 Collegiate Connections

- 5 Reasons to Enroll in a Summer Seminar

2024 Summer Intensive Seminars:

An International Exploration of Piano Teaching Literature

with Leah Claiborne and Luis Sanchez, Seminar Co-Leaders

Teaching Elementary Pianists

with Sara Ernst, Seminar Leader

Upcoming Events:

2024 Summer Intensive Seminars: An International Exploration of Piano Teaching Literature

with Leah Claiborne and Luis Sanchez, Seminar Co-Leaders

Mon Jul 8th

10:00am

Upcoming Webinars:

International Webinar (English, Spanish and Portuguese): Watch Party with the music of Gurlitt, Streabbog, and Granados!

with Sara Ernst, Chris Madden, and Jessie Welsh (04/27/2024)

Sat Apr 27th

1:00pm

Pedagogical Approaches to Advancing Pianists Through Asian Repertoire

with Ross Salvosa, Regina Tanujaya, and Lisa Yui, with Leah Claiborne, host (05/01/2024)

Wed May 1st

11:00am